PREFACE

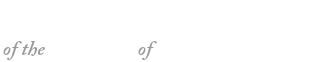

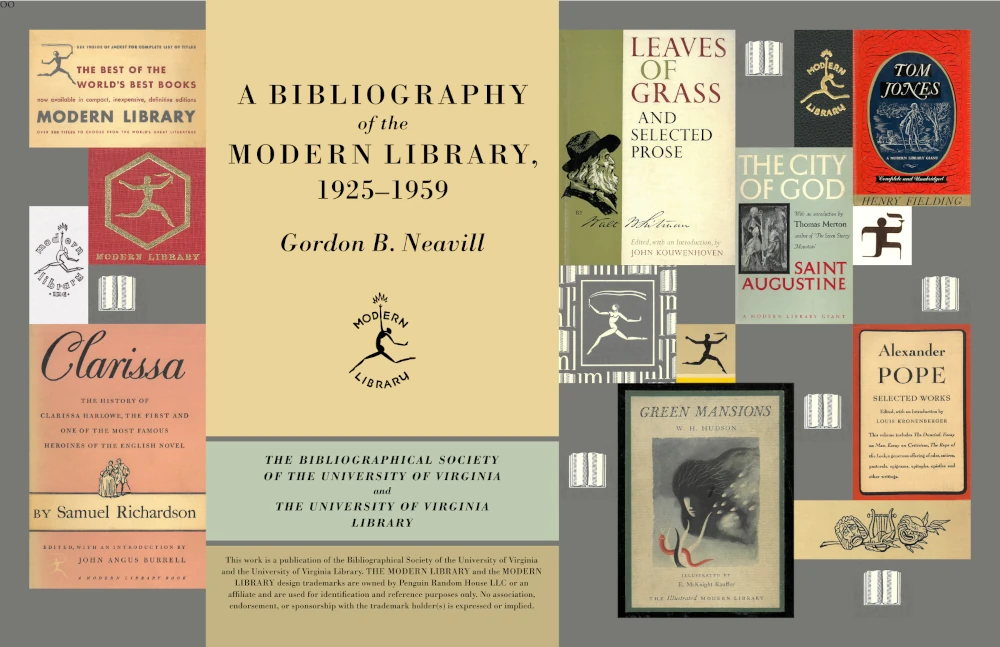

The Modern Library was the most important American reprint series of significant works of literature and thought published in the twentieth century. The series was founded in spring 1917 and published initially by Boni & Liveright. It was purchased in 1925 by Bennett Cerf, a young Boni & Liveright vice-president, who established a new firm, The Modern Library, Inc., in partnership with Donald S. Klopfer. Initially Cerf and Klopfer focused their attention on developing the Modern Library. In 1927 they began to publish and distribute fine limited editions under the imprint Random House. Occasional trade books, including the first authorized American edition of James Joyce’s Ulysses, followed. In 1936 they reorganized the firm as Random House, Inc., and the Modern Library became a subsidiary of its offspring.

The Modern Library differed from British reprint series like Everyman’s Library and The World’s Classics in that its list was not limited primarily to older classics in the public domain but also included modern works that were reprinted by arrangement with the original publishers. Modern Library books were the only inexpensive editions of serious literary works that were widely distributed and readily available in bookstores and major department stores throughout the United States prior to the advent of quality paperbacks in 1953. For most readers of serious books, the Modern Library was the most tangible representation of the literary canon in the American cultural marketplace.

The current project covers the titles that came into the series between 1925 and 1959 during the years Bennett Cerf was at Random House and the Modern Library was the most prolific. This is part of a larger unpublished project covering the entire span of the Modern Library, 1917 through 1986.

The current project contributes to bibliographical knowledge at several levels. It provides a detailed bibliographical description of every title that initially came into the Modern Library over 25 years and follows it over time through multiple printing variants. It describes the major variants of each title, documenting the historical evolution of each title through reset texts, reset title pages, revised translations, introductions added and dropped, redesigned dust jackets, etc. The chronological arrangement, with indications of titles dropped as well as added each year, provides a barometer of trends in literary taste over time, and also reveals trends in printing and publishing practices. The descriptive blurbs on the dust jackets tell us something about the publisher’s conception of works in the series and the intellectual context in which they were marketed to the reading public. The transcription of blurbs from successive jackets reveals changes in the ways Modern Library titles were presented to the public over time.

The publishing history notes, based on research in the Random House archives, constitute a pioneering contribution to our knowledge of twentieth-century reprint publishing. The publishing history and bibliographical analysis of reprint editions have received surprisingly little scholarly attention; yet it is the reprint publisher who generally disseminates a work to its largest audience, who determines whether a work remains in print or ceases to be commercially available, and who may even contribute something to the shaping of the canon. The publishing history notes frequently provide information about reprint negotiations between original publishers and the Modern Library. We learn who initiated discussions, what the concerns of each party were, and what the conventions of reprint agreements were at different periods of the Modern Library’s history. Financial arrangements between the Modern Library, original publishers, and authors are indicated whenever possible, as is information about printings and sales. Much new information is also provided about the publishing histories of individual authors.

The bibliography also contributes something to bibliographical method. Many Modern Library titles remained in the series for decades and were reprinted every year or two. The description of such books presents a number of bibliographical challenges. I have not attempted to track every printing of every title. My approach has been to distinguish bibliographical editions resulting from reset plates and then within editions to establish what I call families of printings based on major bibliographical variants, such as reset title pages and introductions added and dropped. This approach is described below in the Bibliographical Procedures section of the Introduction. I believe it offers a useful approach to the bibliographical ordering of twentieth-century books that exist in numerous printings made from the same set of plates.

The origins of the bibliography go back to the fall of 1976 when I learned about the Random House archives at Columbia University. I was in New York investigating possible source materials for a dissertation on American publishing history. The topic I was considering dealt with an earlier period, and when I became aware of the depth and wealth of the Random House archives, my first reaction was simply that someone would have a lot of fun going through them. It was several days before I considered the possibility that that person could be me. On my last evening in New York, Terry Belanger, then of the School of Library Service at Columbia University, casually mentioned at dinner that the Modern Library series would be a good dissertation topic. I had just enough time before my flight the next morning to stop by the Manuscript Reading Room at Butler Library to confirm that the Random House archives included sources for the Modern Library. When I returned to the University of Chicago I had a new dissertation topic. Dr. Belanger’s interest in the project is woven through its history, and decades later he, as a member of the Council of the Bibliographical Society of the University of Virginia, encouraged the Society to undertake its publication.

I spent fourteen months in 1977 and 1978 immersed in the Random House archives. That research gave me a vast amount of information about the publication of individual Modern Library titles. Toward the end of my time in New York I decided that I would eventually compile a bibliography of the Modern Library in addition to writing a history of the series. I began collecting Modern Library books systematically and thinking about the kind of bibliography I would prepare. I’m a self-taught bibliographer and it took me a few years to figure out what I was doing. Meanwhile I was acquiring more and more books and establishing contacts with other Modern Library collectors. These contacts were facilitated by The Modern Library Collector, a newsletter established in 1981 by Alan Oestreich, a collector in Cincinnati. I have contributed a biannual column, "Bibliographical Notes and Queries," to The Modern Library Collector since 1982 and have benefitted immeasurably from the exchange of information it has made possible.

The bibliography is based on my research in the Random House archives and the examination of nearly 20,000 Modern Library books in my own collection and other major collections throughout the United States. I am grateful to the private collectors who welcomed me into their homes and provided hospitality and assistance. I am also grateful to the National Endowment for the Humanities for a Travel to Collections grant that partially supported visits to seven private collections during the summer of 1992.

David Vander Meulen, Professor of English at the University of Virginia, and the Council of the Bibliographical Society of the University of Virginia under its long-term president G. Thomas Tanselle have given invaluable support for this project for many years and are responsible for leading the effort to publish it. Dr. Vander Meulen’s patience and support have been extraordinary. Anne Ribble, Executive Secretary for the Bibliographical Society of the University of Virginia, and Elizabeth Lynch, Assistant to the Editor for the Bibliographical Society, have contributed in multiple ways to the project. Their ability to identify errors, ambiguities, and similar problems has been invaluable and has led to significant improvements in the text. I also gratefully acknowledge the support of the co-publisher of this work, the University of Virginia Library, which is providing the technology to make the bibliography available to the world. The imaginative and meticulous work of Mike Durbin and his team has given fresh evidence of the UVa Library’s preeminence in digital humanities.

I would like to express my sincere appreciation to my wife, Mary Ann Sheble, who has lived with this project our entire married life and has spent many hours assisting me with the technical and organizational aspects of the project.